Oral History and Narrative Photography of Fateme Sadat Nawab Safavi Life

Guerrilla Lady

Jafar Golshan Roghani

Translated by: Zahra Hosseinian

2020-12-22

When Seyyed Mojtaba Nawab Safavi, the leader of the Society of Fadayeen Islam, and three of his companions were executed by the execution squad and martyred on January 18, 1956, his daughter was 5-years-old. The mother of the girl and her two sisters was Nayereh Sadat Ehtesham Razavi. The girl was brought up by her mother and her maternal family, that is, Nawab Ehtesham Razavi (one of the first-degree convicts of the Goharshad Mosque incident in 1935), until she got married her mother's cousin, Seyyed Abolhassan Fazel Razavi, and gave birth her only daughter named "Umm Hani".

The documentary "Fateme", produced, researched and directed by Masoumeh Nour Mohammadi, narrates briefly the story of her life in 30 minutes. The director visited اher and asked her, who is now a seventy-year-old woman, to present in various regions of her social, artistic and military life and to narrate her story in front of the camera. The documentary is based on oral history and first-person narration of memories and the course of her life. Although along with some images, several people appear in front of the camera and reminisce for a few minutes, but the narration and expression of memories of others has been used unprofessionally. The four or five people who narrate their memories are unknown people, and their relationship with Fateme Sadat and even their place in her life are unclear. Perhaps their narration of their memories is merely visual in order to get the audience acquaint with the faces of other people, in addition to the main character, in the film, and to present very brief and sometimes undated confusing narratives.

However, with all its shortcomings, it should be said that the director has dealt with one of the neglected topics in historical, military and artistic research in this documentary, which is the positive point of her work. Apart from this short documentary, no narration of Fateme Sadat's long and tumultuous life is presented. She is 70 years old (born in 1950). Both because of her relation with two important and influential figures in contemporary Iranian history, namely her father Seyyed Mojtaba Nawab Safavi and her grandfather Seyyed Nawab Ehtesham Razavi, and because of living with her exiled husband in Sistan and Baluchestan province in Pahlavi period for years, also traveling to the United States with her husband and studying computer science, traveling to Lebanon and her guerrilla training and campaigning activities, accompanying Shahid Chamran in the early days of the revolution and the Irregular Warfare Headquarters, journalism activities, especially traveling to Libya and meeting and interviewing Muammar Gaddafi, photographing war scenes and the presence of warriors, military presence on the fronts, especially in the operation to conquer Khorramshahr is certainly a huge treasure trove of memories, observations and unspoken things, which have not been expressed and have been preserved in her mind for many years. It can be regretted, surely, that none of these aspects have been paid full attention to in this documentary; as if the director was in a hurry to tell a story about her in the shortest possible time.

According to the documentary, Mrs. Fateme Sadat Nawab Safavi narrates her life as follows: From her childhood, due to the lifestyle of her parents and grandfather, she became acquainted with combat and jihad and grew up under the influence of the same lifestyle. "Our life combined with struggling from the beginning. We grew up with fighting since childhood... I was a kid and wanted to be very strong. In order to train myself, to train my soul for this resistance, I may have often acted in a way that only I decided on my own. I remember, for example, [when] I was a 3-4 year old girl, often slept on mosaics in the yard at night. I wanted my body to get used to hardships." During the days she went to school, at the time of the Algerian struggle against French colonialism, "I said my mother: My dear mommy, I want to defend the rights of the Algerians and to fight against oppression along with them. Since childhood, the counter-oppression was inside me."

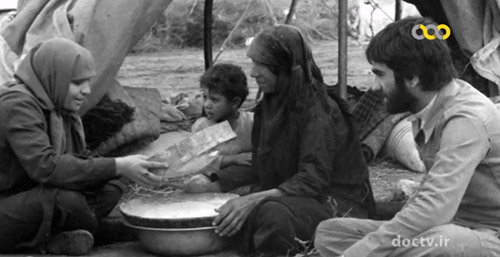

After marriage, she was forced to live with her husband in a village around Zahedan, near Chabahar and the Persian Gulf, for seven years. "As my husband had written a very important article during his military service, he was sent to the farthest parts of Iran, the most deprived parts of Iran, that is, Baluchistan of Zahedan, the south of Baluchistan. I mean if you look at the cat-like map of Iran, it was located at the cat's tail! It was one or two hours distance from Chabahar. Before the revolution, there was no roads there at all. [My husband] was a poet. He was a writer. He had a positive energy that made everyone, from all different classes of the society, to love him." She does remember very well how they first arrived at that village called Baftan "The first time we came to Baluchistan, when Hassan [= Abolhassan], had to spend his literacy corps course there, we came upon two Kapars. They were given us as a place for village teacher. With the help of students, a small mud room was built... It was the first time a school was established in this village. There were no tables, chairs, blackboards, pencils, notebooks and books at all. If someone wanted to provide all these things from the city, it might have taken a long time and it was not possible for us at all. Also, at that time, there was no telephone and such things that we was able to call Education Office and asked them to provide us such things." One of Mrs. Nawab Safavi's students and her husband, Vali Mohammad Kiani, remembers well that, "I remember their salary was 1,200 Tomans. In order the students come to study, she and her husband gave their salary to them in 10 or 5 Tomans. At the beginning, their students were 10-12 some, then they increased to 40-50." Fateme Sadat, who is still immersed in the love and affection of living with her husband and child at those years, says: "We, me and Hassan, loved this region so much that my daughter also loved there unconsciously. She wore Baluchi clothes and when she was among Baluchi children, was not much different from them… How pleasure it was. Hassan performed his first Adhan in front of the very Kapar; now the village children still recall that Adhan... At the very beginning of our lives, we spent our honeymoon here. I think it was one of the sweetest honeymoons in the world... there was nothing more beautiful than this. His footsteps have always been in this area. All hearts still love and cherish him."

After Fateme Sadat contracted malaria, they were forced to leave there after seven years. Later, the villagers named the school Shahid Fazel Razavi Primary School. After that, for he was very effective in establishing unity in the village, the villagers changed the school name to Vahdat Baftan Primary School by their own decision.

After recovering from illness, Fateme Sadat traveled to the United States with her husband for higher education and returned to Iran after four years; then she went to Qom to achieve his lifelong dream of studying religious sciences and at the same time to be a journalist.

After the victory of the Islamic Revolution, coincidence with the Kurdistan crisis in 1979, she went there as a reporter for the Kayhan newspaper and interviewed Ezaddin Husseini, Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, and Jalal Talabani, who later became President of Iraq. The interview was published in the newspaper on November 26, 1979. She then went to Libya and interviewed Gaddafi about the disappearance of Imam Musa Sadr. In this regard, she also traveled to Lebanon.

After the start of the war, according to her, "I went straight to Khuzestan, to visit the late Chamran. Because Ms. Chamran (Ghada Jaber) was one of my close friends and I respected Dr. Chamran and his thoughts very much. I told the late Chamran: ‘Doctor, I want to defend my country, my religion and my revolution like a soldier alongside the fighters.’ Dr. Chamran agreed because he was familiar with my spirits. He gave me a Jeep Land Rover, an RPG and a Kalashnikov rifle and some guns to go to war."

According to three warriors of those years, "she made a huge ammunition belt for herself, which were full of magazine Kalashnikov rifles and carried about 300-400 rounds of ammunition and some grenades… We gave her a trench and jokingly said, do we send someone to keep guard of you? She said, do it for yourself. At that time, she, as a woman (no matter who was her father), felt obliged to go to the front and fight side by side with other warriors... she was a skilled woman. That is, she was trained. I saw many women who so-called fought out of necessity. We even have many martyrs. But she was a trained one... once she was very close to the enemy. She had approached almost 100 meters of the enemy when she was taken lots of shots, but was able to escape with a motorcycle. Dr. Chamran’s troop always fought at the first line of the army forces. In other words, in addition to being fighters, they almost sacrificed themselves."

Then, Fateme Sadat recalls when she was fighting in the Deb Hardan area near Ahvaz, "there was a field where the Iraqis had tanks... but we didn’t have a single tank there. We had nothing. Believe me, it was the most oppressive war and God didn’t allow them to approach forward, that is, they feared our fighters so much, and really God didn’t want them to advance; in fact they could not. Imagine, we, in 4-5 people or 3-4 people groups, moved forward very hardly through canals to reach a distance where we could shoot a 60mm shell. "We even didn’t see where it was, just knew the Iraqi tanks were on the other side." During her time in the war, she did not hesitate to do anything; as one of the residents of Susangard recalls of 1981, “When we were in Susangard hospital, she were looking for corpses and wounded and martyrs of our own forces. You did it too, if you were there. In fact, I said myself, lest she slip and fall somewhere. She followed the corpse, followed the wounded, and followed the stretcher for the martyrs."

Fateme Sadat mentions the spiritual manifestations of the fronts as follows: "I think it was the day of Tasu'a or before it. Those days, Imam Hussein (AS) was completely understood and perceived. Our children were martyred one by one, and you quite felt that the army of Yazid was against the army of Imam Hussein (AS). It was beautiful. It was very strange. As matter of fact, that day was one of the most beautiful days in the world. It was noon and it was very hot in Khuzestan. The fighters were very thirsty. No one's canteens had water. Everyone could be torn to pieces at any moment. I prayed, God, save and protect these soldiers. I saw a Turkish army RTO who sang a dirge in Turkish about Hazrat Zainab (PBUH). She recalled of the conquest of Khorramshahr on May 24, 1982, "That day the siege was broken suddenly, and we were the first to enter the city. The wounded were seen everywhere. The Iraqi tanks were burning ... it was felt that all was injured. It was as if the city was injured, the trees were injured, the houses were injured, and the walls were all demolished... I realized that the Saddamists who evacuated the Khorramshahr, had destroyed all the houses in the city. Actually Most of the houses. Then they shaped the iron beams of houses liked a dome, a hill. It was totally a strange malice. It was very upsetting. However, we took back the city; as Dr. Chamran said: ‘In order to keep the national pride of our youth and not allowed to be damaged, we must take back Khorramshahr.’"

As a child, she was interested in painting and photography with a simple small camera, and she liked to record the world with her mental image. So, during her time on the fronts, she also took photographs. "I always carried a camera in my hand. Dr. Chamran, may he rest in peace, was very happy when he saw that I took some photos of the war scene. He said: ‘Mrs. Nawab, these are all historical documents, revolutionary documents... Take photos.’ I took many photos for the sake of the fighters. Because they were so happy when I took pictures of them and I could see that happiness in their faces. You know, they felt that their sacrifice was seen and recorded, and that was very interesting to me. I took most of these photos just for the sake of them. In each scene, I experienced life and death, perhaps a hundred times. I have faced death a hundred times, for example, to shoot a short movie. I feel that I can still at least see those beauties with my eyes, that is, all those scenes were very strange to me. I go twice in those memories, in the world of that time. A strange world which may not be repeated."

Fateme Sadat, who has a lot of love and devotion to Shahid Chamran, has many memories of her time with him. She describes him as follows: "I think there was always a great energy around him that we were always moving under the support of that energy. He was a refuge for all of us, for all the warriors, and that energy still exists. Dr. Chamran is valuable because of his spirituality. No matter what was his position, whatever he wanted to be, graduated in America; he was an inventor and had many inventions; importantly, he had the highest level of knowledge... The poor were like his children. He hugged, kissed, and caressed the fighters of the front, who were covered in dust all over their heads and faces. He didn’t say that they are dirty and I am in my headquarters now. Which in charge person now acts like him? Once, for example, an Iraqi soldier had been arrested... One of our soldiers slapped his ear in order to make him to talk, but Dr. Chamran got angry and cried out that why do you hit a prisoner? Who allowed you to do that? This makes Dr. Chamran as a role model for everybody... At the beginning of the war, I was interrogating an Iraqi sergeant who confessed that, ‘We don’t sleep at night for fear of Khomeini's soldiers.’ and this insomnia was caused by Dr. Chamran’s troop."

She, who is now in charge of the Shahid Nawab Safavi Cultural Institute, considers herself as a God's Pauper and one who seeks the truth, according to a book by Nikos Kazantzakis. Accordingly, she believed that: "We must stand up and resist. If we hurt, if anything happens to us, we must resist. It is impossible for a person not to stand up, and to give up, that is, to surrender to the enemy."

Number of Visits: 3577

The latest

Most visited

How to send Imam's announcements to Iran

In the first part, the issue of funds, Hajj Sheikh Nasrallah Khalkhali - who represented most of the religious authorities - was also the representative of Imam. In Najaf, there was a money exchange office that cooperated with the money exchange offices in Tehran. Some of the funds were exchanged through him.Operation Beit al-Moqaddas and Liberation of Khorramshahr

After Operation Fat’h al-Mobin, we traveled to Kermanshah and visited Sar-e-Pol-e-Zahab before heading to Ilam. During Operation Beit al-Moqaddas, the 27th Brigade was still receiving support from the West. We maintained contact with individuals who had previously worked in Area 7 and were now leading the brigade. It was through these connections that I learned about Operation Beit al-Moqaddas.Memoirs of Hujjat al-Islam Reza Motalebi

Hujjat al-Islam Reza Motalebi is a cleric from Isfahan. Before the revolution, he was the imam of the Fallah Mosque – which was later renamed Abuzar Mosque. By his presence and efforts, Abuzar Mosque soon became a base for supporters of the Imam and the revolution. After the victory of the revolution, he played a role in uniting forces and maintaining political vitality in southwest Tehran.The Necessity of Receiving Feedback in Oral History

Whenever we engage in a task, we naturally seek ways to evaluate our performance — to correct shortcomings and enhance strengths. Such refinement is only possible through the feedback we receive from others. Consider, for instance, a basketball player whose shots are consistently accurate; should he begin shooting blindfolded, his success rate would rapidly decline, as he would be deprived of essential feedback from each attempt.