An 'unrecognized history' of black Vermonters given prominence

17 June 2013

Newly designed Vermont African American Heritage Trail brings attention to the contributions of black Vermonters

African Americans have maintained a significant role in Vermont history, but their place often has been unrecognized, historians say.

The Vermont African American Heritage Trail, announced last month by the Department of Tourism and Marketing, is a guide to the personal stories of black Vermonters who helped to change the state’s identity.

Some were the first to hold positions formerly attained only by people of European descent, and others participated in Vermont life in schools, churches and farming communities.

The trail includes sites from Brandon to Brownington, Ferrisburgh to Woodstock and a dozen other museums, cultural sites and historic markers along the way.

It’s not intended as a specific route for visitors to follow, but planners hope the variety of sites will bring tourists to the state.

“The sites have existed for decades but were not linked together in such a way as to attract the attention of multicultural markets,†said Curtiss Reed, executive director of the Vermont Partnership for Fairness and Diversity, in Brattleboro.

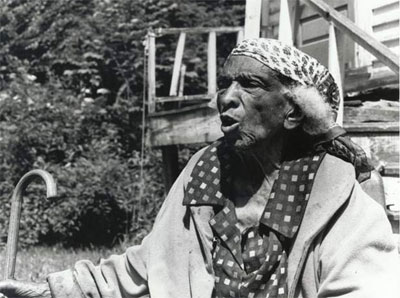

Daisy Turner's oral histories are featured as part of the Vermont African American Heritage Trail. Her recordings are available at the The Vermont Folklife Center in Middlebury. / Photo courtesy of the Vermont Folklife Center

Reed collaborated with Catherine Brooks, the tourism department’s Cultural Heritage Tourism Director, to determine ways to grow the economic impact of African American visitors. Brooks worked with researchers, writers and designers to create a website and map.

“This is an opportunity to change the narrative of Vermont to the rest of the country,†Reed said. “Vermont is known as one of the whitest states. That is true geographically, but in terms of social justice, it belies the numbers.â€

Rokeby Museum

One of the trail sites closest to Burlington is Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh. The museum tracks two centuries of the Robinson family — farmers, naturalists, artists, authors and abolitionists.

Rokeby director Jane Williamson said the site is the most documented stop on the Underground Railroad in Vermont and perhaps in the country. The “railroad†was a network of routes and safe houses used by escaping slaves in the 19th century to travel safely to a destination in non-slave-holding states.

Abolitionists Rachel Gilpin and Rowland Thomas Robinson seen here in an image from Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh. The museum is a stop on the Vermont African American Heritage Trail. / Courtesy of Rokeby Museum

In 1823, Alexander Twilight was the first African American to earn a bachelor's degree from an American college or university at Middlebury College. He later served in the state legislature. Middlebury College is a stop on the newly designed Vermont African American Heritage Trail, as is the Old Stone House Museum where Twilight built a dormitory. / Photo courtesy of Old Stone House Museum Archives

There was more to the story than just a route for travel, Williamson said. At Rokeby, the Robinson family housed and gave employment to former slaves.

The popular understanding of the railroad is that it was much larger and better organized that it actually was, Williamson said. “The Robinson’s son, Rowland E. Robinson wrote a story published in The Atlantic Monthly about a fugitive slave sheltered in Vermont. People based their ideas of the railroad on that story.â€

Rokeby will open a new exhibit, Free and Safe: The Underground Railroad, on May 19 in a newly constructed visitor center.

“The exhibit will provide an authentic story of the Underground Railroad from the fugitives’ point of view and from the human side,†Williamson said. Letters in the Rokeby collection all were about slavery and abolition, and they allowed the staff to separate fact from fiction, she said.

Celebrating Black History Month, Rokeby will host a program Feb. 24, featuring a half-hour excerpt from the public television series The Abolitionists. Williamson and a panel of local history teachers — William Hart of Middlebury College and Kevin Thornton and Amani Whitfield of the University of Vermont — will describe Vermont abolitionists and their connections to people featured in the series.

Historic marker in Hinesburg

A ruggedly based historic marker stands in a clearing at the intersection of North Road and Lincoln Hill Road in Hinesburg, commemorating Early Black Settlers of Hinesburg.

“On this hill from 1795 to 1865 thrived an African American farming community,†begins the tribute placed there by the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation.

The settlers cleared the land, joined the local Baptist church, fought in the Civil War and exercised their voting rights. Their descendants owned land and contributed to the local economy until the late 20th century.

The black farmers’ stories might have stayed hidden if not for Elise Guyette and her research for graduate degrees in history and for her book Discovering Black Vermont: African American Farmers in Hinesburgh, 1790-1890, published in 2010.

Guyette combed records in the Hinesburg town vault where she found land transactions and business, school, town meeting and church records. In a story for the Vermont Secretary of State’s Archives Month in 2010, Guyette wrote, “To me, the vault holding the records of early Hinesburgh was like a proverbial underground chamber full of rough-cut gold, diamonds, and rubies, waiting to be discovered.†The records contained incredible gems about the lives of farmers on Lincoln Hill, she wrote.

On Sept. 29, 2010 about 60 local residents and descendants of the original farming community gathered to celebrate the dedication of the historic marker.

Vermont Folklife Center

The Vermont Folklife Center in Middlebury has made preservation of the spoken word the core of its work. One of its best-known archives of oral history is that of Daisy Turner and her stories.

Turner was one of 13 children born to parents who were former slaves. She recorded oral recordings of her family’s history, going back three generations to Africa.

“Our immediate contribution to the heritage trail is the interactive media kiosk,†center co-director and archivist Andy Kolovos said. “People may sit and see text and photos of Daisy Turner on a screen, using a cased iPad.â€

The kiosk will show four videos, which also may be viewed online. The center also has about 100 hours of interviews with Turner, taped by center founder Jane Beck and digitally preserved with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“One of the amazing things about Daisy was her memory,†Kolovos said. “She was a very animated and exceptional storyteller.†Turner died in 1988 at the age of 104.

Grafton History Museum

Daisy Turner has a connection to the Grafton History Museum, too, having been born and raised in Grafton. It contains documents that describe the life of Alexander and Sally Turner, Daisy’s parents. Alexander, a former slave, was able to purchase 150 acres of farmland and build a home for his large family.

The museum is open Thursday through Monday Memorial Day through Columbus Day, and daily during foliage season.

Middlebury College

The college is listed on the heritage tour because of its pioneering history of degrees earned by African American students. It granted a masters degree in 1804 to the Rev. Lemuel Hayes, the first such degree given to an African American. In 1823, Alexander Twilight was the first African American to earn a bachelor’s degree from an American college or university. He later served in the state legislature, and in 1986 the college renamed one of its buildings Alexander Twilight Hall in his honor.

Brandon Museum and Visitor Center

The Brandon Museum explores the active anti-slavery movement that existed in the town and in Vermont, and the impact of the Civil War on its townspeople.

For the heritage trail, the museum has added a 10-minute presentation of the video “Brandon and the Slavery Question.â€

The museum and visitor center are located at the birthplace of 19th century statesman Stephen A. Douglas; it is are open from mid-May to mid-October.

Hildene, in Manchester

Hildene, the family home of Robert Todd Lincoln, tells the story of varied ways the actions of Abraham Lincoln and his son, Robert, impacted the lives of generations of African Americans.

An exhibit titled Many Voices highlights the voices of the Pullman Company (of which Robert Lincoln became chairman), passengers on Pullman trains, and black porters who serviced the train cars.

Hildene also offers tours of the 412-acre estate, the mansion, gardens, farming operations and a 1903 Pullman car.

Old Stone House Museum, in Brownington

The museum includes six buildings on 55 acres, centered on a massive four-story stone building completed in 1836 by the efforts of Alexander Twilight, as a dormitory for students of the Orleans County Grammar School, where he was principal, even while many African Americans still were slaves.

Museum collections manager Liz Nelson speaks of the building as an “architectural masterpiece.†It was the first granite public building in the state.

Nelson said it holds copies of Twilight’s sermons, given in the Brownington Congregational Church, and personal stories of Twilight’s life. Other buildings include Twilight’s home, two more houses and a traditional barn; they feature exhibits of the history and sociology of Orleans County.

The museum is open for guided tours Wednesdays through Sundays, May 15 to Oct. 15.

People may view Vermont’s 1777 Constitution, the first in the nation to prohibit slavery, said John Dumville, historic sites operations chief, Vermont Division of Historic Preservation.

Justin Morrill Homestead Historic Site

Exhibits at the Morrill homestead in Strafford display historic papers in the residence, designated a National Historic Landmark. Exhibits feature the Land Grant College Acts, which opened higher education to blacks and Native Americans, Dumville said.

Other locations on the heritage trail are the River Street Cemetery in Woodstock; the George Washington Henderson Historic Marker in Belvidere; The Martin Henry Freeman Historic Marker in Rutland; the Rev. George S. Brown Historic Marker in Wolcott; and the Coventry War Memorial in Coventry.

A map and list of sites on the Vermont African American Heritage Trail can be found at http://bit.ly/WZXPLz.

Number of Visits: 3682

The latest

Most visited

Hajj Pilgrimage

I went on a Hajj pilgrimage in the early 1340s (1960s). At that time, few people from the army, gendarmerie and police went on a pilgrimage to the holy Mashhad and holy shrines in Iraq. It happened very rarely. After all, there were faithful people in the Iranian army who were committed to obeying the Islamic halal and haram rules in any situation, and they used to pray.A section of the memories of a freed Iranian prisoner; Mohsen Bakhshi

Programs of New Year HolidaysWithout blooming, without flowers, without greenery and without a table for Haft-sin , another spring has been arrived. Spring came to the camp without bringing freshness and the first days of New Year began in this camp. We were unaware of the plans that old friends had in this camp when Eid (New Year) came.

Attack on Halabcheh narrated

With wet saliva, we are having the lunch which that loving Isfahani man gave us from the back of his van when he said goodbye in the city entrance. Adaspolo [lentils with rice] with yoghurt! We were just started having it when the plane dives, we go down and shelter behind the runnel, and a few moments later, when the plane raises up, we also raise our heads, and while eating, we see the high sides ...The Arab People Committee

Another event that happened in Khuzestan Province and I followed up was the Arab People Committee. One day, we were informed that the Arabs had set up a committee special for themselves. At that time, I had less information about the Arab People , but knew well that dividing the people into Arab and non-Arab was a harmful measure.