Kobra Nemati Tells of Memories of School

Interview: Faezeh Sassanikhah

Translated by Ruhollah Golmoradi

2021-9-14

Kobra Nemati was born in Ilam in 1956 and has served in education for 28 years. Some of her years of service coincided with the imposed war. The iranian oral history website's correspondent spoke with her so that she talks about those years.

■

Where were you when the war broke out?

I entered education in Aban (October or November) 1979. I taught sociology and mostly religious sciences early, but when the war broke out, I was principal of Tarbiat High School and also principal of night High School of Parvin Etesami.

Before the war began, there was news that Iraqis had come to the border. The first martyr of Ilam, Ruhollah Shanbei, was a Pasdar (force of IRGC) who died a martyr on the border. However, we did not take presence of Iraqis seriously, we had neither experience, nor had we seen the war closely.

How were Ilam's schools held and managed in these circumstances?

Classes were held until the bombings became intense. I don't want act hypocritical, but I wasn't afraid until 10 to 12 aircrafts came toward the city and I was scared. When aircrafts came above the city, our classes were held; when bombardment increased, Department of Education announced that it was no longer permissible to hold classes and that schools should be emptied and you leave the city. Some students were afraid and didn't come, but classes were not closed. The first bombardment of Ilam in the first year of the war took place at 10 p.m. and they fired a place near to Saderat Bank. Four people died a martyr and some were injured. It was still early in the war and the fighting had not escalated; at the end of the war, 10 to 15 aircrafts came together. Because we were near the border, aircrafts would come easily, bombard and launch missiles.

During the bombing, students and teachers come out of classes screamingly. Everyone ran away toward the walls and under the pillars. After the aircrafts left, we would go back to class. We had an Arabic language teacher who I think he has deceased. One day in the classroom when sound of bombardment was heard, this gentleman quickly came down the stairs and opened his hands and stood under the staircase. He looked funny. The children weren't really scared, but he was so scared.

What year did you settle in tents and villages?

I don't remember the exact year, but many times we left the city. We were in the city for one or two years, then there was a meeting in Department of Education and they informed us to go to the surrounding villages. We would go to nearby villages and often camp.

We had a caretaker named Esmaeil Rostami, who was an amazing person. He did not value his home and his life as much as he valued school. God bless him, he kept his ear on the ground to know when we should go, as soon as he realized that we were going to leave the city and camp in the villages, he would go before us and prepare the environment. One day, without informing me, he had loaded the school supplies and took them with himself. Because he was from nomad, he had camped and then informed me where he had settled.

Which villages were you mostly stationed in?

We usually took our homes to the village with parents. The roads were dirt and there was dust on the way. When it was cold and rainy, the conditions became very difficult, but at night we would come to nearby villages. As soon as I got, I would inform Department of Education that I was, for example, in Chalsara or, for example, Goleh Jar, which was a little further away. The more bombardment, the more distant areas we would go and rent a house or room there. Sometimes I would go alone and rent a room myself, because my parents were in Chalsara and couldn't come with me. For example, I would go to Goleh Jar and rent a house there and go to work in the morning. One day we were on our way to Chalsara with the assistant principal of the school when the bombardment started. We would go around in the water and sludge.

How was to run a school in those circumstances?

In those situations, the students would disperse; some students would come to where we were going and some would go to other villages. We would set up classes and the office in tents and the children would come and sit on moquette. As long as the weather was good, classes were held in free space and teachers taught, but when it was cold, we usually took classes in village schools, and when the bombardment was intense, we didn't hold classes; that is the children wouldn't come and some of them would go to the nearest school where they lived. In these circumstances, we would only take important exams such as the university entrance exam and Teacher Training, etc. in their planned time. These exams were held in poultry, cattle shed and such places. We would clean, arrange tables and chairs, and prepare there. God rest soul of that caretaker, he worked very hard and did what we had to do. Department of Education through IRIB announced place of exams. When inspectors came and saw the order there, they encouraged us very much. I have many certificates of appreciation from that period.

Did you collect aids at school for the fronts?

Yes. Students were very active in sending cash and non-cash donations such as edibles, shawls and hats for warriors. They helped enthusiastically the front in any way they could. We would collect donations at school and then send them to Department of Education.

In addition to cash and non-cash donations, I would send Shahid Chamran's books to the front at my own expense. Shahid Chamran had revolutionized me spiritually. I liked to share his writings with others too. My bitter memory of the war was martyrdom of Chamran. His martyrdom disturbed me roughly and was deadly to me. When Dr. Chamran died a martyr, I felt absolute solitude because I had read his memoirs and manuscripts. I liked his prayers and his spirit was very interesting to me in expressing memories of Kurdistan and the siege of Sanandaj. Because he was so dear to me and his memories and personality influenced me much, I would send these books to the warriors.

I was interested in the political situation and issues of the day, and I regularly had meetings for the children and gave speeches for them. As long as the school was established, every year we celebrated days of The Fajr Decade in any way with available facilities. The students collaborated on decorations, writing essays in the wall newspaper, writing declamation and poetry, and holding ceremonies. During the year, we also collected money for Palestine.

Did you cooperate directly with the war support headquarters in Ilam?

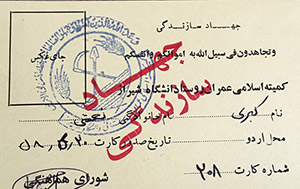

I used to work with Jahad-e Sazandegi (Jihad of Construction) for a while, where most of our work was in literacy, and our assistance through Department of Education. Before the war, I was in school until evening and went to the surrounding areas of the city at sunset. For the children, there was a literacy movement class and I taught them. My teaching was free and there was no serving or overtime payment. Jahad-e Sazandegi did a lot of works to eliminate deprivation in the villages. I had been working with them since I was a student in Shiraz studying sociology. Its office in Shiraz was under supervision of Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi. The location of the office was as far as I know Faculty of Engineering at Shiraz University. Jahad-e Sazandegi was then doing health, medical, economic and cultural affairs related to the villages, and I was also working there and we went to the villages. For example, there was a girl with cleft lip who had lost her parents. We brought her from the village and delivered to the medical school. When they operated that girl because she didn't have anyone, I was with her. After graduating from Shiraz University, I returned to Ilam and went to Ilam’s Jahad-e Sazandegi.

During the war, Ms. Fatemeh Nahidi came to Ilam on behalf of Jahad-e Sazandegi to help people of deprived villages, and I would go with her on the days when I had free time.

I don't know if she was medical or nursing student, but she did therapeutic tasks, because the villages were very deprived, she went to health center and helped the disadvantaged there. I am a Kurd and I was her translator from Kurdish to Persian, and she came to our house at night. Because there was no dormitory for women, she was introduced to me on behalf of Department of Education.

Noting a point is not useless; I graduated after the Revolution, but for a while, because there were protests and mood of the revolution, the university was closed, and we came to our homes. After the revolution, when we returned to the university, we saw that every room had become a party for itself; MKO, Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG), fans of the Kurd’s People, etc. I don't remember all the names.

The majority, minority, and pervasive propaganda had been used; there weren’t such things previously. I attended in one of the meetings of MKO, and after the meeting, when we wanted to get out of the lecture session, we saw that there was a crowded place and they said, "Let's get a card, I said, "For what?" they said, "For membership,” that is they wanted to recruit and say they are in favor of us, I went to see what was going on, but I and many others didn't get cards. The next time, the pro-Kurd’s People students held a meeting in Kurdish dresses, I went there one or two sessions, and even though I am very interested in political issues, I felt that it didn't match my beliefs and I didn't go anymore, but then I cooperated with revolutionary forces like Jahad-e Sazandegi.

Did your salary help your family during the imposed war?

Fortunately, my father didn't need this money and he didn't have anything to do with my salary. My father was a wealthy of the city at the time, and he was a businessman and a mercer. Of course, at that time, the shops were not just selling a special material; my father was a mercer, but he also sold dry edibles. He had many lands and flocks outside the city in shepherd's hands, and we had a large garden. Before the revolution, he had also gone to Hajj.

My father believed that my salary was my own and did not ask any question about it. I even remember one day that we sit on the terrace, one of my brothers said jokingly, "Shouldn't we know how much you're paid?" That time not much time had passed from my recruited. My father got so angry and told him, "Why are you asking these questions?"

I have to say that when we were out of town, businessmen who sold basic materials and supplies of people camped on the roads and people went there for shopping.

How many siblings were you? No one from your family died a martyr during the war?

We are four sisters and five brothers, that Ali Ashraf, my youngest brother, died a martyr in Operation Valfajr-5 in Changuleh area on February 18, 1984. At that time, we were almost out of town and in Chalsara. I was on the street that day and wanted to go home when a relative stopped in front of me in a car and my nephew was with him. He said, "They say a person called Nemati has died a martyr.” Because there were other Nemati families, I did not take it too seriously until we went to my brother's house, which was a little further down, and we saw that yes, they were moving carpets. I realized something had happened to them. One of my nephews, Ruhollah Rashnavadi, died also a martyr. My sister, he and I had the honor to go Hajj. He was just 19, 20 years old, but had a high mystical spirit. In Tawaf of Kaaba, I felt he was not with us and was elsewhere. The only souvenir he bought for himself from Mecca was a shroud. In short, when we returned from Mecca, in 1987 he was exposed to a chemical bomb in Operation Shakh-e Shemiran Chemical and died a martyr there. His martyrdom was even harder for me than my brother's.

Where were you when the war was over?

After Operation Mersad, the sky was full of insider aircrafts. We were home at the time and we didn't go out; the situation was so awful. After almost one or two days, the city became empty and everyone went to Kermanshah, which is near Ilam. The radio kept declaring that people would be stable and resist, etc., but there was some negative news that was painful and they said the city is falling. Alhamdulillah, Operation Mersad was over. When Imam Khomeini accepted the resolution and said, I drank the poison cup, it was very heavy for me to hear this sentence.

Thank you for giving your time to the Iranian Oral History Website.

Number of Visits: 4441

The latest

Memoirs of Hujjat al-Islam Reza Motalebi

Hujjat al-Islam Reza Motalebi is a cleric from Isfahan. Before the revolution, he was the imam of the Fallah Mosque – which was later renamed Abuzar Mosque. By his presence and efforts, Abuzar Mosque soon became a base for supporters of the Imam and the revolution. After the victory of the revolution, he played a role in uniting forces and maintaining political vitality in southwest Tehran.The Necessity of Receiving Feedback in Oral History

Whenever we engage in a task, we naturally seek ways to evaluate our performance — to correct shortcomings and enhance strengths. Such refinement is only possible through the feedback we receive from others. Consider, for instance, a basketball player whose shots are consistently accurate; should he begin shooting blindfolded, his success rate would rapidly decline, as he would be deprived of essential feedback from each attempt.Sir Saeed

The book “Sir Saeed” is a documentary [narrative] of the life of martyr Seyyed Mohammad Saeed Jafari, written by Mohammad Mehdi Hemmati and published by Rahiyar Publications. In March 2024, this book was recognized as one of the selected documentary biographies in the 21st edition of the Sacred Defense Book of the Year Award. The following text is a review on the mentioned book.Morteza Tavakoli Narrates Student Activities

I am from Isfahan, born in 1336 (1957). I entered Mashhad University with a bag of fiery feelings and a desire for rights and freedom. Less than three months into the academic year, I was arrested in Azar 1355 (November 1976), or perhaps in 1354 (1975). I was detained for about 35 days. The reason for my arrest was that we gathered like-minded students in the Faculty of Literature on 16th of Azar ...