Oral History Workshop – 2

Memory

Shahed Yazdan

Translated by M. B. Khoshnevisan

2022-12-13

The oral history website is going to provide the educational materials of some oral history workshops to the audience in written form. The present series has been prepared using the materials of one of these workshops. As you will see, many of the provided contents are not original or less said contents, but we have tried to provide categorized contents so that they can be used more.

Memory

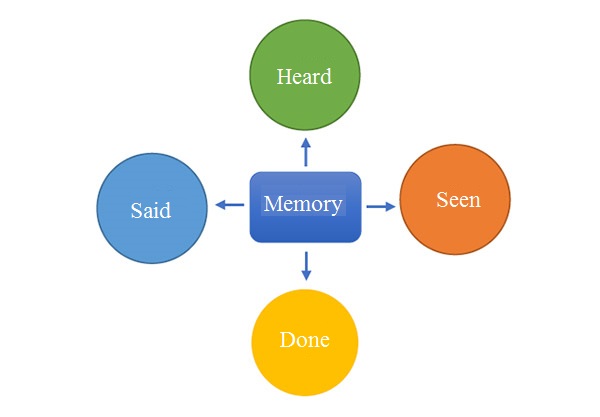

What the narrator has seen, heard, said or done is called memory.

For example, if the narrator says: "I captured several people in the Karbala operation 5", it is a memory, but if he says: "In the Operation Val-Fajr, the combatants achieved victory", it is a knowledge.

In memory, the subject is the narrator.

Memory is classified based on different models. In a division, memory is divided into oral or written.

In another type of classification, memory is divided into absolute and bound.

An absolute memory is a memory that has no boundary. For example, the narrator says: "One of my comrades and I went on a night operation and destroyed a tank and came back." This is an absolute memory, but in order for this memory to be useful for oral history, it must be bound to place, time, description and all its surrounding points. In this example, the narrator must specify which operation at night, on what date, with what weapon, with whom, etc., has been carried out so that it can be used in oral history.

In oral history, the bound memory is useful; but absolute memory is also used in storytelling. Absolute memory in oral history is weak because it cannot be verified.[1]

Another division of memory in terms of form is literary memory and historical memory. Literary memory describes, for example, "a beautiful summer moonlit night..." but if the same part of the memory is said in this way that "the fourteenth night of the lunar month coincided with ... and the moon was shining in the sky..." This kind of memory will be historical.

For oral history, we need bound oral memories in historical form, and if we can extract this type of memory from the narrator's mind, we will reach the desired result.

Although it is easy to say, even the best interviewers will gain at most 20 minutes of pure memory within an hour. Since our opposite party (narrator) is a human being, it will not be an easy task to obtain memories that are favorable to us.

In the discussion of memory, there are two other definitions of memory and narration, which are mostly mentioned in universities (especially the science of psychology), and since we are dealing with them in the following discussion, they need to be defined.

Memory is our mind, but all the events that happened to us during our lifetime have not remained in our mind and we only remember a part of them. According to psychologists, the whole mind is memory, and what remains in our memory is called memory. What we express from that memory is also called narration.

In oral history, the purest raw material is to get an accurate narration from memory. It is very difficult to get an accurate narration, and the narrator may narrate a single memory in different ways at different times according to different conditions.

Narration of memory by people changes in different situations. The best narration is the one that is narrated without any love or hatred and with the accuracy of memory. This is one of the difficulties of oral history and it is the hard work that must be done to get accurate narrations from pure memories.

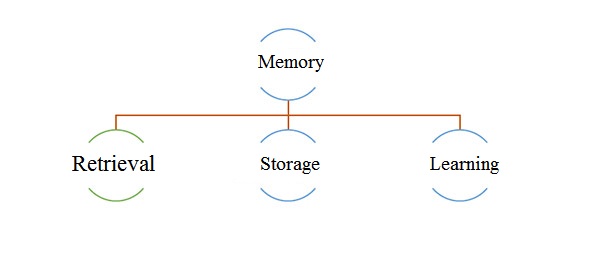

The memory of every person has three parts: learning, storage and retrieval. The art of the interviewer in an interview is to activate the retrieval part. If we can activate the narrator's mind to retrieve his or her memories, we will succeed.

Number of Visits: 2557

The latest

- The Necessity of Standardizing Oral History and Criticism of General Mohsen Rezaei

- The 368th Night of Remembrance – Part 1

- Oral History News of Khordad 1404 (May 22nd – June 21st 2025)

- Najaf Headquarters Human Resources

- The Embankment Wounded Shoulders – 12

- Annotation

- The 367th Night of Memory– 5

- The Founder of Hosseiniyeh Ershad

Most visited

Operation Beit al-Moqaddas and Liberation of Khorramshahr

After Operation Fat’h al-Mobin, we traveled to Kermanshah and visited Sar-e-Pol-e-Zahab before heading to Ilam. During Operation Beit al-Moqaddas, the 27th Brigade was still receiving support from the West. We maintained contact with individuals who had previously worked in Area 7 and were now leading the brigade. It was through these connections that I learned about Operation Beit al-Moqaddas.Memoirs of Hujjat al-Islam Reza Motalebi

Hujjat al-Islam Reza Motalebi is a cleric from Isfahan. Before the revolution, he was the imam of the Fallah Mosque – which was later renamed Abuzar Mosque. By his presence and efforts, Abuzar Mosque soon became a base for supporters of the Imam and the revolution. After the victory of the revolution, he played a role in uniting forces and maintaining political vitality in southwest Tehran.The Necessity of Receiving Feedback in Oral History

Whenever we engage in a task, we naturally seek ways to evaluate our performance — to correct shortcomings and enhance strengths. Such refinement is only possible through the feedback we receive from others. Consider, for instance, a basketball player whose shots are consistently accurate; should he begin shooting blindfolded, his success rate would rapidly decline, as he would be deprived of essential feedback from each attempt.Sir Saeed

The book “Sir Saeed” is a documentary [narrative] of the life of martyr Seyyed Mohammad Saeed Jafari, written by Mohammad Mehdi Hemmati and published by Rahiyar Publications. In March 2024, this book was recognized as one of the selected documentary biographies in the 21st edition of the Sacred Defense Book of the Year Award. The following text is a review on the mentioned book.