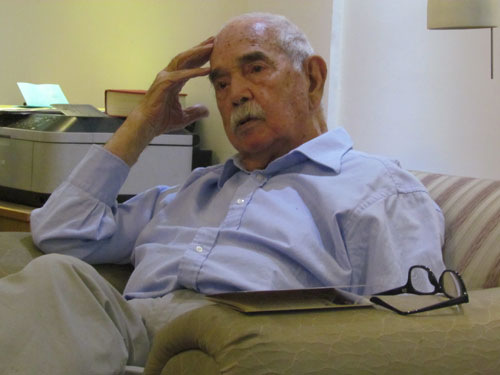

“In the Alleys and Streets” with Dr. Abbas Manzar Pour

Interviewed by: Mohammad Mehdi Mussa Khan

Translated by: Mohammad Bagher Khoshnevisan

2015-07-26

Note: Last year, we found the opportunity to talk intimately to Dr. Abbas Manzar Pour the writer of “In the Alleys and Streets” in the house of his respected son. Although the talk took more than three hours, it was so intimate and sweet that we did not feel the passage of time. “In the Alleys and Streets” has so far been republished for several times (five times) and warmly welcomed by the readers. It is among the useful works in the area of anthropology and social history of the city of Tehran. In the following interview, we asked and heard about his book and other historical issues in the past century. Here is the excerpt of the interview with Dr. Manzar Pour:

Mussa Khan: For the beginning, tell us a little bit about yourself:

Manzar Pour: I was born in Hamam Golshan Alley in Tehran’s 12 District near the house of Sheikh Mohammad Reza Tonkaboni the father of the prominent religious figure Mr. Falsafi. I studied in three different schools in Tehran until the fifth grade of secondary school. For continuing the education at that time, we had no other way but to go to Dar al-Fonoun (Polytechnic) School. So I went there inevitably.

Mussa Khan: In what field did you study?

Manzar Pour: I intended to continue my education in a literary field, but my father forced me to study in Natural (experimental) field. It is worth mentioning that at that time I was in charge of the Youth Organization of the Tudeh Party in Dar al-Fonoun School. After passing the diploma exams, I took part in Concours (nationwide exam for entering the universities) and was admitted in dentistry field of Tehran University. I was also an activist and a secretary of the Student Organization of Tudeh Party. But I severed my cooperation with the party before the coup of August 19, 1953. I think the regime’s security forces had infiltrated the organization of youth and student. After graduation, I went to the health department of Khorasan’s 8th Division for military service. I spent good times there because I was relieved of a series of cumbersome bindings and also had no9 political activity. After completing my military service, I went to the Health Ministry and was appointed as the head of the dentistry section of the Health Department of the town of Fouman in northern Iran. Then I served in Damavand’s Health Department for seven years and after that I went to Varamin and finally was retired with the salary 8000 Tomans per month. .

Mussa Khan: What factors caused you to think of writing such book?

Manzar Pour: It is an interesting question. When I was a pupil, I always wrote good compositions. In the sixth secondary course, I only got the grade of 20 in the lesson of composition. Before the revolution, I wrote articles for Kayhan daily.

Mussa Khan: on what issues?

Manzar Pour: Most of them were critical-social ones. Thus, I was not far from the atmosphere of writing. From the viewpoint of the late Iraj Afshar, I had a modern prose and was close to the language of the public. One of the prominent literary figures of the country narrated that he had gone to visit the late Afshar. He was studying a book. When he had asked him why you did not pay attention to us, the late Afshar had answered that he was reading a book that he could not do anything else until finishing it. That book was “In the Alleys and Streets”.

Some two decades ago, my wife suffered from cancer and left the country for Switzerland for operation. After surgery, she was fine for fifteen years but again suffered from cancer. I went to Britain for curing and taking care of my wife who was living with my daughter. I took care of her for five years but she finally died. When I was abroad, my son suggested me to write my memoirs and I started doing this. At first I wrote just for my son to read, but then Mr. Qadimzadeh the then Head of the Publications of the Guidance Ministry in a trip to England, saw my notes and enjoyed the. So the first volume of my memoirs was published by the Guidance Ministry. After a while, he asked me to write the second volume and I did this. Then I wrote the third one. In 2008, three volumes were published in volume under the title “In the Alleys and Streets”.

Mussa Khan: Have you ever seen such examples before you started writing the memoirs?

Manzar Pour: Jalal Al-e Ahmad has an article about the passing away of the famous poet Nima which I see similarities to my work. It is worth mentioning that Jalal al-e Ahmad was a friend of my cousin Habib. I saw him in the Habib’s shop. Jalal al-e Ahmad met him every week or twice a week.

Mussa Khan: It’s a good time to remember the late Morteza Ahmadi.

Manzar Pour: Yes, God bless his soul. I knew him.

Mussa Khan: Did he use you for his books?

Manzar Pour: No, we talked to each other but he was in another path.

Mussa Khan: What was the work of the late person who did in the field of the idioms of the old Tehran?

Manzar Pour: He collected the idioms used in the houses which were common in female circles to some extent. Many books have been written about Tehran like a book by the late Jafar Shahri (which has many errors) which has just described Tehran’s appearance. But unfortunately no attention has been paid to the people’s behavior and social relations. This aspect of the old Tehran has been paid attention to in the book “In the Alleys and Streets”. I have not looked at Tehran’s buildings but have tried to describe the relations between the people as it has been. I should say that we had respected people in the past. I remember that most of the people believed in religious issues.

Mussa Khan: What was your aim of writing this aspect of Tehran’s history?

Manzar Pour: I had no aim but I loved history. I am interested in history very much. I registered an aspect of the history which unfortunately has been ignored by most writers. I should say regretfully that I do not know anybody except myself who writes the culture of such districts as Esmaeel Bazzaz.

Mussa Khan: To me, you define history in another way. From your viewpoint, history is the life of people not the life of statesmen and kings.

Manzar Pour: Yes, exactly, the first character that you see in the book is Mr. Reza. A person who despite inheriting of a large wealth did not stick on it and other characters in the book were all normal people of the community.

Mussa Khan: One of the interesting points you have paid attention in the book was the question of the Loutis (hoodlums), Lats (villains) and the champions of the old Tehran. What was the reason for your attention to this stratum of old Tehran?

Manzar Pour: One reason was that my father was one of them. Unfortunately at present the word Luti is synonymous with Lat (villain). But the two are different. I love the Lutis. As I said, the first character in the beginning of the book is Mr. Reza who was a Luti. Other Lutis have also been introduced in the book. If we take a look at the history of our country, the Lutis have been very influential in the community like Yaqub Leith who was a member of ‘Ayaran group which helped the poor. I must say that the Lutis were in the cities and their origin was urban. In the era of the famous poet Hafez, we see Rendan alley. The lat Zarrinkoub has a book with same title. The alley has been real and the Lutis were in the alley. In the war between Shah Shoja and Amir Mobarezeddin, the Lutis backed Shah Shoja. In continuation, you see the Constitutional Movement. Sattar Khan and Baqer Khan were among the Lutis of Tabriz and everybody admits their role in the movement. Iranian mysticism also belonged to the cities not villages. For instance, Mowlana came from the city of Balkh and Attar had an urban root. On the other hand, my father was in relation with many Lutis including Hossain Ramezan Yakhi. His status was very higher than Tayeb Haj Rezaee because Tayeb was not so Luti. I and my father knew Tayeb very well. But I should say that the character which is now depicted from him is not correct.

Mussa Khan: What about Shaban Jafar?

Manzar Pour: I did not dispraise Shaban Jafari very much in the book. He was from Darkhoongah district. I think his shortcoming was that he went to Ahmad Abad and insulted Mosaddeq. Shaban was not a ver bad person. Many member of Tudeh Party were angry at me because of this description but I had described the person I had seen. He served for the friends. He was not an original Luti. The original Luti of Darkhoongah was “Mustafa Divaneh”. He went to "Tek Tek Zoorkhaneh" (traditional gymnasium) for Bastani sport (a traditional sport that originated in Iran). Today, the athletes are paid for exercising but at that time, some tradesmen paid the daily costs of the sport center in order to continue its work.

Karimi: If we want to present a definition from the Lutis, how do you describe them? What were their characteristics?

Manzar Pour: At the first degree, a Luti is a merchant, it means that he is self-employed and does not work for the government. Everyone at every time who worked for the government was kicked out of the Luti group including Shaban Bimokh (Jafari). During the course of history, there were oppressive rulers and the oppressed and real Luti do not support the oppressor. Second, the Lutis respected the elders and the people's chastity very much. Third, they helped the poor as far as they could and did not expect anything.

Mussa Khan: So, the Lutis established order in the districts?

Manzar Pour: Yes, for example, a person who wanted to go to Mecca, he left his family to a Luti due to the long journey (it might took six months) in order to protect them. The typical example of this was the character of "Dash Akol".

Karimi: In your book, you have said that this conception of Luti belongs to Tehran's folklore. You mean that we did not have Lutis in other cities during Pahlavi?

Manzar Pour: The thing to which have been referred in the book belongs to post-constitutional Tehran.

Karimi: Can this type be seen in other places?

Manzar Pour: I have not seen this in other places. I should say that after the coup of August 19, 1953, I have not seen a Luti in the real sense of the word.

Karimi: You mean that the coup caused this class of the community to be omitted?

Manzar Pour: To me, you should not underestimate the impact of the America culture. There were young Lutis both inside the National Front and the Tudeh Party before the coup. After the coup, with the arrival of the American system, money and capital were considered the most important factor. After the Second World War, the Americans with their films and advisors imported their culture to Iran more than before. The culture which attached more importance to money, was against the Lutis' deed, and for this reason, the Lutis were gradually omitted from the society. You'd better know that the Lutis never quit their prayers, even if they drank alcoholic drinks.

Karimi: Was this type of Luti deed related to men?

Manzar Pour: No, Here we should also name female Lutis. One instance of them was two of my own aunts. My older aunt (Masoumeh) had five children and her husband had died. She was a tailor. She sewed clothes and went to the notorious district of that time (Shahr-e now) and under the cover of selling the clothes met the women there and if she saw a girl or a woman had been deceived, she bought them. She did not have enough money but the people of the neighborhood respected her very much and helped her. After buying, she brought them to her house and taught the rules of praying, fasting as well as sewing. The people of the neighborhood who knew my aunt found husbands for the women. After marriage, each of these women went to a place, acting as a center for the faith and religion. My other aunt was named Khadija. Her husband had died and her groom had been disappeared so his three children lived with her. In order to earn her living, she worked very hard. She received no money from her brothers. To me, she was a Luti. I have seen such women a lot and unfortunately since our country is a patriarchal one, we have fewer materials about our women.

Karimi: Persons like Tayeb usually carries out religious works.

Manzar Pour: As I said Tayeb was not a Luti in the real sense of the word. I have written about the characteristics of a Luti in my book. Of course, Tayeb helped others but not without blackmailing.

Mussa Khan: One of the districts that you have dealt with in your book is Abmangol neighborhood. You have written a lot about Abmangol. It is popularly known that the neighborhood is an original one with faithful and religious people. Is it true?

Manzar Pour: It is correct to some extent. It had almost lots of religious sites but not very much. I lived a long time in Abmangol neighborhood and knew many of its people, like "Aseyed Es'haq" one of the most famous writers of amulets and prayers in Tehran to whom I have referred in my book. I think there was a Luti there whose name was Javad Zehtab. The neighborhood had faithful merchants. Nonetheless it had also villains. It had both good and bad people. It was not an assorted neighborhood.

Karimi: You said that after the coup of August 19, 1953, the culture of Luti deeds decreased in the society. But we have a cinema called Farsi Film. In this cinema, characters like Fardin and Nasser Malek Motiei were seen clearly. Didn't they display the character of a Luti?

Manzar Pour: Not at all. Such films were copied from Indian ones superficially. The only movie that showed the characteristics of the Lutis was "Gavazn-ha"(The Deers).

Karimi: So, why did the people welcome these low-quality films?

Manzar Pour: Because they were depicted the stories which were romantic to a great extent and far from the realities of the society. The low-class people saw many of their dreams in such movies. Thus, they welcomed them.

Mussa Khan: One of the most important places during the uprising of June 5, 1963 was Ray Street. Were you there at that time?

Manzar Pour: I had been to Germany for PhD education and I was not in Tehran. But I read and followed the news.

Mussa Khan: After returning to Iran, did you ask the people about the event?

Manzar Pour: I asked my wife about it. When I went to Germany, my wife and children went to my stepsister in the city of Qom. The house of my sister was exactly beside the house of Ayatollah Khomeini. Mr. Mustafa Khomeini was a friend of my brother-in-law. He had a butcher's shop near the holy shrine of Hazrat Masoumeh (SA) and supplied the meat needed for the house of Ayatollah Boroujerdi. He said that Ayatollah Khomeini went to his shop and bough a little meat for his family. When the Shah agents came to the house of Imam Khomeini on the night of June 5, my brother-in-law who had been in the yard was hearing that he told the agents loudly, "I am Khomeini, do not bother anyone." Then, the agent brought him. When they went, his servant shouted that Imam was arrested. In the morning, the people gathered in the holy shrine of Hazrat Masoumeh (SA) and the event of June 5 happened.

Mussa Khan: As the last question, when your book "In the Alleys and Streets" was published, what was the feedback?

Manzar Pour: I had many calls which showed the people's attention to it. As I said the fisr volume was financed by the Guidance Ministry, but soon I was asked to write the second one. The book was warmly welcomed by the experts in a way that the late Zahraee, the Head of Karnameh Publications offered me to write a book about the Lutis and Lats(villains) and he planned to do something but left this world. At present the books is going to be republished for the fifth time. I am very happy that I see the youth have warmly welcomed the book. I hope I could have a small share in the familiarization of the young people with the social history of their country.

Mussa Khan: thanks a lot for answering the questions patiently.

Persian Source

Number of Visits: 9124

http://oral-history.ir/?page=post&id=5460