War Atmosphere, Being Unbelievable for the Next Generation

Interview with Hojattoleslam Saeed Fakhrzadeh about oral history

Interviewer: Mr. Sayyed Qasem Yahoseini

Translator: Mr. Mohammad Baqer Khoshnevisan

Q: How did you enter the war fronts?

A: The anti-revolutionary movements in

For the second time after the liberation of Khorramshahr, I along with my classmates in the seminary went to Khorramshahr and  barriers and fortifications the enemy had built in Khorramshahr. The enemy had planted the iron beams of the railway inside the earth vertically so that a parachute couldn’t land. We took several photos from them and they became interesting photos. I still have some of them.

barriers and fortifications the enemy had built in Khorramshahr. The enemy had planted the iron beams of the railway inside the earth vertically so that a parachute couldn’t land. We took several photos from them and they became interesting photos. I still have some of them.

When we were walking in

Once again, we were sent to western war zone. At first, I was in charge of distributing the goods and the presents that the people had sent to the war fronts. Later, I was engaged in cultural and propaganda works. We launched religious classes, and were welcomed very well. Sometimes, I escaped propaganda works and went to the headquarters of other units for visiting combat areas and liberated bastions. I also listened to the combatants' talks and enjoyed their memories.

Q: Was it at this point that you felt you should register your war memories?

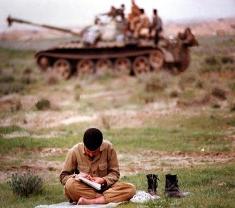

A: Yes, I started to register the memories since that time. I felt that nobody in the atmosphere of behind the fronts, knows about these events. There was a line between the front and behind it in which the two sides of the line were not aware of their circumstances. The people in the behind of the war fronts were spending their daily lives despite numerous shortages and in the other side, everybody was engaged in fighting and bombardment. I decided to establish a contact between the two sides. So, I began registering the memories. I wrote the events on a daily basis, and specified the area very precisely. I had a Kurdish black jacket that a friend of mine had been presented to me. I had also another friend who had trousers with the same color of my jacket. He told me, “Either give me your jacket or take my trousers so that this jacket and trousers belong to one.” His appearance looked like the Kurds. I said, “You can place yourself as a Kurd.”

front and behind it in which the two sides of the line were not aware of their circumstances. The people in the behind of the war fronts were spending their daily lives despite numerous shortages and in the other side, everybody was engaged in fighting and bombardment. I decided to establish a contact between the two sides. So, I began registering the memories. I wrote the events on a daily basis, and specified the area very precisely. I had a Kurdish black jacket that a friend of mine had been presented to me. I had also another friend who had trousers with the same color of my jacket. He told me, “Either give me your jacket or take my trousers so that this jacket and trousers belong to one.” His appearance looked like the Kurds. I said, “You can place yourself as a Kurd.”

We were driving with him when a mortar hit the car. He was jumped from the car. As we couldn’t stop, he said, “Keep driving, I’ll find you.” We went and all of my notes remained in the pocket of that jacket. After some time, a car belonging to the information guys passing that area picked him up and asked him, “Where are you going?” He said, “We are searching and gathering information.” They got suspicious of his type and appearance and asked, “Where do you want to go?” He said, “to the headquarters of 27 Division.” They said, “But we go first to our headquarters and then our friends take you the Division.” When they took him there, they interrogated him. They asked him to show an ID. But he answered, “My ID and other documents are in the jacket that I have given to my friend.” They asked him to empty his pockets. He did so but did not allow they touch the jacket’s pockets. He says, “I am not allowed to do this, it belongs to my friend.” Finally, they took his jacket and saw my report-like notes. This person whose name was Sabouri was even about to be executed. They wanted to execute him as a spy but eventually his identity was specified and released. But they didn’t take the notes back to him. So, all of my registered notes was torn down there.

Q: What happened that you were involved in writing the memories of the war? And where did you start from initially?

A: Before I came to the Revolutionary Guards, I had a friend named Ameri who was a clergy. He was engaged in cultural activities in the Committee and provided the ground for us to enter Zanjan Committee. We were involved in cultural activities for about one and a half year. There was a palace in SharAra that it seemed Khorram had been going to present it to Shah’s son, but it had not fully been built. Its architecture was like a ship. It was said some time that this palace had been Bani Sadr’s office. Then, the Committee guys took control of it and we worked there. Later, I made friend with a person named Mohammad Rahimi in

Q: You mean that a special arrangement had been carried out from the beginning for registering war events and the incidents of the Imposed War period?

A: The memories’ notebooks were distributed in millions that were like a booklet. There was a map at the end of the booklet showing the border towns of

Q: How long was it that the Office of Registering War Memories had started its activity?

A: There was a group in the head office of the Revolutionary Guards called “War and Front Propaganda” worked as a special team. All the propaganda items including fillets, photos on chest, flags and like these were provided by this group. The group was comprised of two or three. Misters Seyyed Javad Mousavi and Mohammad Qasem Foroughi were in charge of printing and publishing all the items. One of other friends had been assumed their distribution. They were an independent group working under the general directorate of the Guards Propaganda. At that time, the Guards Propaganda had two head offices in the western and southern areas. One was the Headquarters of Southern Front and War and Najaf whose head office was in

Q: With which of the head offices did you work?

A: I worked with the head office in

Q: Did you need training for entering the system of registering memories?

A: No, not at all. I was criticizing the situation of the group when they offered me to cooperate with them. We designed and printed special forms through which we could have the memories of every person with regional and personal characteristics. We also registered them on the tape. Actually we had created an almost complete archive. At the same time, we tried to heighten the quality of recordings. I as a permanent member was in charge of recording the memories. When there was a military operation, Mr. Musavi locked the doors and said, "We have nothing to do here anymore".

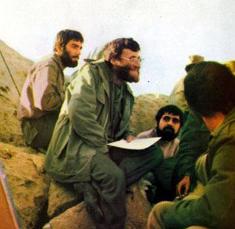

We arrived in the war zone with an arranged plan. We registered and recorded the combatants' memories in different parts. Misters Foroughi and Musavi also registered these memories with a tape recorder special for reporters. We transcribed these talks and kept in the archive. I offered that it should be an office of registering memories in every headquarters. I went to

Q: Did you follow a special subject in the interviews or posed questions about war sporadically?

A: Our strategy was to ask them as many questions as possible. Why did come to fight? Where have you come from? What was your motivation? What have you done? Where have you gone? What events have you seen? What other memories do you have? and many other things. The interviews were in the form of Q&A and sometimes took a long time.

I remember the Baneh commander had come from Telecommunication section. Later he was martyred. The people of

Q: certainly conducting such interviews had been accompanied with difficulties. Tell us about those difficulties.

A: One of the problems was that the guys of Intelligence-Protection said theses issues had to be kept in secret. Once they detained me and seized my tapes. They said such works have not been defined for us. We said we have a mandate. Of course, because the mandate had been outdated, they said it is not valid anymore. They asked us to extend it but we didn't have the opportunity to come back to the Headquarters and get a new one. That was why we were among the first detainees in

They detained us in a room and started interrogating. Who are you? Who has told you to conduct such interviews? And questions like these.

They seized our tapes and said, "We would give it to you in the Headquarters". And in the Headquarters, they said, "We would deliver them in

Q: Had it ever happened to you that someone gave his diary and says these are my memoirs?

A: There were very few people who had diaries and registered their memories. I had many conversations with Martyr Kaveh in Mehran Operation. He was convinced to recount his  memoirs after Kaveh Operation. Martyr Kaveh was from

memoirs after Kaveh Operation. Martyr Kaveh was from

In many cases, while interviewing, the guys were affected and become excited and then weeped. We cut the interview to let them come out of that atmosphere. Then we continued the interview in another conditions. Sometimes, the continuation of the interview was postponed to other day.

Q: Did you have a special technique for recording and registering the memoirs or since the events were fresh, the interviewees had presence of mind?

A: When I wanted to interview a group, after conducting two or three interviews, we could have access to the whole event. We found all the matters related to that subject. So we questioned about various issues and discussed the surrounding matters. For example, if we wanted to interview about Baneh and the events related to it, we knew all the matters precisely and directed them to the main path.

Q: What was the average age of your colleagues at that time?

A: Around 18 to 20. They all were men. The situation at war front was somehow that you could hardly find a woman. I personally did not see even a woman.

Q: Were your questions specific and particular or you had special questions for every situation and character?

A: We didn't have any written question. Most of them were in mind. However, we had provided a series of questions for the interviewers so that they could put themselves in the environment of interview. Questions like information about his unit and division, in which operation he has taken part, questions form war scenes, the memoirs of his friends, the martyrdom of fellow combatants, etc.

operation he has taken part, questions form war scenes, the memoirs of his friends, the martyrdom of fellow combatants, etc.

Q: Did you face with untrue news and memories about war events?

A: Rarely. But we faced. Someone said a memory about an operation that they were supposed to retake an area from the enemy. He explained it so sweet and full-of-clashes that we enjoyed a lot. And at the end, the enemy was captured and the banner of Islam was hoisted in the highest area. After the recording was finished, he said, "All were lies. We were defeated in the first moments." I asked, "Why did you explain like this?" He said, "It's bad to disgrace Islam and say that we have been defeated. That's why I said we gained victory. I said, "We are writing history, we haven't come to publicize."

Some in their memoirs called the enemy as mean. We said, "We don't publicize. We don't seek to chant slogan. We want to record history as it has happened." We talked to them about one hour to justify them. In general, it was hard. The initial talks for shifting the message were very important. We notified them of the way of interview. We had obtained good experience after several months. Sometimes, as soon as we turned the recorder on, he was frightened somehow. In order to remove this stress, we tried to start from normal questions. If also a situation came up, we made our verbal contact more intimate in a satiric way and by joking. And then, we said, "Look, my dear, your voice would be transcribed in a written way and it is not going to be broadcast anywhere." Before starting to record, one was speaking very fast and fluently, but as soon as the record button was pressed, his tongue faltered and couldn't speak smoothly.

Q: Were there any person who showed resistance against interview and recording and you had to stop recording?

A: Some said that this subject was personal and that no need to record it. We played a trick too. We pretended that we have turned the recorder off, but it was in fact on. A person named Mr. Shahidi who was martyred later said, "I tell all forces under my command to have interviews with you. But let me alone. I'll tell these guys to talk to you as much as they can and to fully cooperate with you." I said, "OK, but I have a few questions that you should answer." I have recorded some of his sentences. He said, "I am the commander of these guys, but I am actually regarded a disciple of them."

Q: How did you code and sort these tapes?

A: We wrote exactly whatever was necessary: At what time, how many minutes, where and who. We conformed that information on the cover of the tape. Everyone who conducted an interview, the number of his interview was written on the cover of the tape, for example, Fakhrzade 2, Fakhrzadeh 85, etc. We didn't conduct a new interview with a new tape. They were all in sequence. Some told memories for 20 minutes, some told a small memory and some others had no memory to tell. We recorded these successively and one after another and at the end, delivered to the Archive. The Archive section had also its especial numbers.

Q: At what time in the morning did you usually started to work?

A: We woke up for the Morning Prayer and then after that since we didn't have special military ceremony in the mornings, went to have breakfast. Others had breakfast after special military ceremony and when they entered the unit, we started our work. We continued as much as we could. Averagely, I took around two or three hours of cassette tapes everyday. I personally conducted two thousand hours of interviews about the war. Our salary was as the same as a Basiji, that is 2400 Tomans. We had no overtime or things like this.

I personally conducted two thousand hours of interviews about the war. Our salary was as the same as a Basiji, that is 2400 Tomans. We had no overtime or things like this.

Q: What was the fate of these tapes?

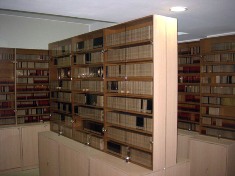

A: We packed the tapes after the interviews and sent them to

Q: Has it ever happened the battery of your recorder had been de-charged while recording?

A: Yes, there was shortage of battery in those years. I was seeking to find recorders with better quality, but at that time, the shops didn't have a special tape recorder for reporters. If our recorder got out of order while recording, we used a plus one. We sent the out-of-order recorders to

When the tapes reached to

Q: Were these sisters the members of Revolutionary Guards?

A: No. They received salary from Basij. I chose my forces among those Basijis who came from the Revolutionary Guards. After they were archived, a group reviewed the content of the tapes, and selected the subjects for the memoirs’ book. Mr. Foroughi was in charge of Utilization section whose output was very slow. It didn’t match with input section at all. When I entered the complex, we had 100 to 150 hours of interview, but when I delivered it in 1367 (1985) and around 20,000 hours of interviews had been conducted. It was a five-person team whose personnel were continuously changed.

Q: Were these interviews with the combatants or the tape of recording conversation?

A: Just interviews, which was of course created in the form of branch-to-branch. Misters Ashtiani and Anbari were a team that formed the Arabian part of the interviews in order to conduct interviews with Iraqi POWs with the help of some Arab language people of Khuzestan province. Theses interviews were transcribed and archived by other Arab language people. Some 800 hours of interviews were conducted. We did everything to attract the confidence of the POWs. For example, they didn’t have enough cigarettes for smoking. I talked to the head of Tobacco department, Mr. Sameti who was also the professor of my religious lesson. He gave us cigarettes to distribute among Iraqi POWs or paid money. We bought some shirts and gave them. Then they sat and told their memories.

Another branch was interviewing the guys of Badr Corps. They were those Iraqis who had differentiated right from wrong during the war period. They cooperated with us. Some 700 hundreds of interviews were with them too. Another branch was the war disabled. For example, we arranged to interview those disable persons who were in special hospitals or other places.

Q: Did you have any interview about the families of the martyrs?

A: We had chosen another approach for the family of martyrs. We had provided diaries in relation with the martyr or martyrs of that family. We had posed about twenty questions and asked them to attach if any document they had hold from the martyr in trust. We also gave this diary to the families of POWs and missing persons. The Guards guys said, “We have a Cooperative section. Give these diaries to us to distribute for you.” We gave them to the Guards Cooperative and they distributed throughout the country. Our problem was in  relation with gathering the dairies. Most of the members of the Cooperative were sisters. Since they were continuously changed, lots of problems were emerged in collecting these diaries. It wasn’t useful whatever we wrote letters to the authoritis. We ourselves formed a team for following the work in the provinces. Mohammad Zeinolabedini who is now in charge of the Documentary section of IRIB Channel 4, assumed this responsibility to travel different provinces. We’re told in the provinces, “We thought they were homework notebooks and gave them to children to write their homework.” Some others said, “We thought you had given them to us to write whatever we like.” Another place said, “The notebooks are still in the store and haven’t been distributed yet.” We concluded this is not possible through organizational process. At the same time, I had mentioned in different opportunities the importance of this matter clearly. It was because of its importance that the sisters asked us to leave this work to them. You don’t know what the martyrs’ families told us. Those few diaries that were returned had been written very briefly and it was clear that the martyr’s wife or mother had written them. However, some interesting things were found among them. I reread the interesting ones. One of these diaries belonged to a family whose Basiji son was a POW. They had written from their son’s daily notebook. For example, “I arrived at the unit today. Our commander was not a good man. The guys complained this. I quarreled with him and was detained.” He had explained all the events of his military service moment by moment until the day of the operation when he had been captured. He had written, “I will go to take part in the operation tomorrow. If I came back, then I would continue. If not, I’ll give this notebook to those who can reach it to my family.” In addition to this, his family had written briefly about his education and life. I can say for sure that we were the only organization that had a specific and clear program for collecting the memoirs of the legendary POWs who had been released.

relation with gathering the dairies. Most of the members of the Cooperative were sisters. Since they were continuously changed, lots of problems were emerged in collecting these diaries. It wasn’t useful whatever we wrote letters to the authoritis. We ourselves formed a team for following the work in the provinces. Mohammad Zeinolabedini who is now in charge of the Documentary section of IRIB Channel 4, assumed this responsibility to travel different provinces. We’re told in the provinces, “We thought they were homework notebooks and gave them to children to write their homework.” Some others said, “We thought you had given them to us to write whatever we like.” Another place said, “The notebooks are still in the store and haven’t been distributed yet.” We concluded this is not possible through organizational process. At the same time, I had mentioned in different opportunities the importance of this matter clearly. It was because of its importance that the sisters asked us to leave this work to them. You don’t know what the martyrs’ families told us. Those few diaries that were returned had been written very briefly and it was clear that the martyr’s wife or mother had written them. However, some interesting things were found among them. I reread the interesting ones. One of these diaries belonged to a family whose Basiji son was a POW. They had written from their son’s daily notebook. For example, “I arrived at the unit today. Our commander was not a good man. The guys complained this. I quarreled with him and was detained.” He had explained all the events of his military service moment by moment until the day of the operation when he had been captured. He had written, “I will go to take part in the operation tomorrow. If I came back, then I would continue. If not, I’ll give this notebook to those who can reach it to my family.” In addition to this, his family had written briefly about his education and life. I can say for sure that we were the only organization that had a specific and clear program for collecting the memoirs of the legendary POWs who had been released.

When Iranian POWs were released, I found the address of this man. He worked in a cultural section of an office in relation with the released POWs. I said hello to him and asked him, “Do you know me?” He said, “No.”. I said, “We were fellow combatants.” And I started to explain whatever I had in mind from his diary. He said, “When I was a POW, I reviewed my memories everyday in order not to forget them. But in where of these events are you? Why don’t I remember you at all?” He was getting crazy. I said, “Wait a minute.” And then I showed him the diary and said, “We had made familiar with you through this diary. Now I want you to take us to Iraqi concentration camp with your memories”. He said, “The importance of the memoirs is very clear for me. You’ve never seen me. But by reading my memories, you became so accustomed to me that I was sure you’ve always been with me, but I don’t remember you. I understand the significance of such memoirs.” His name was Mohsen Dargahi.

In that period, there was no writing culture for registering most of the memories. They had to be recorded and registered orally.

Q: The output of these memoirs is seen in Payam-e Enqelab (Message of Revolution), Omid-e Enqelab (Hope of Revolution) and like these. Tell us more about these written memoirs.

A: Yes, It was used in both of them. It was also published in a book. There were various books that I don’ have in mind. Most of the memory books published in those early years were about these memoirs. Mohammad Qassem Forughi who is still active in publishing works, was in charge of printing theses books. Our work continued until the end of the war and I was away from religious studies in those years.

There was a line between war fronts and behind the front and the two sides of the line didn’t know about each other’s situation. In the behind of the front, despite shortages, the people were earning their lives and on the other side, they were engaged in fighting and bombardment. I just wanted to establish a contact between the two sides. That is why i started to write memoirs.

Soureh Monthly Magazine/ No.36/ Jan, Feb, March 2008

Number of Visits: 7775

http://oral-history.ir/?page=post&id=4208