Da (Mother) 3

The Memoirs of Seyyedeh Zahra HoseyniSeyyedeh Zahra Hoseyni

Translated from the Persian with an Introduction by Paul Sprachman

2022-07-05

Da (Mother)

The Memoirs of Seyyedeh Zahra Hoseyni

Seyyedeh Zahra Hoseyni

Translated from the Persian with an Introduction by Paul Sprachman

Persian Version (2008)

Sooreh Mehr Publishing House

English Version (2014)

Mazda Publishers

***

II. The Translation

As has been often said, translations by nature are a series of compromises that betray original texts. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that those able to contrast the original to the present translation will find treachery in every chapter. Some of the ways the English version of Da differs from the Persian, or pales by comparison to it, are described below.

Footnotes: Da’s publisher anticipated criticism of the work’s failings as oral history by annotating the text with a number of footnotes, some of which are taken verbatim from historical sources. One of these is an explanation of the “Arab insurrection” (gha’eleh-ye ‘arab) in Chapter 3 (pages 60–63 in the original).37 This footnote does not appear in the translation. It was felt that a personal memoir was not an appropriate place to raise the issue of Arab separatism in southwestern Iran, a complex and controversial topic that comes up frequently in the modern history of the country. In addition, the excessively detailed account of the uprising that took place at the beginning of the Revolution breaks the flow of Zahra Hoseyni’s story. Apart from this footnote, almost all other notes in the original have been translated as is, incorporated in the text, or consigned to the glossary that follows the translation.

To Die or Be Martyred: Halaliat: Having translated three fiction works on the Iran-Iraq War,38 I have often thought about how to render shahid (“martyr”) or be-shahadat rasidan (“to be martyred”). As they do in all Sacred Defense writing, casualties in Da—both civilian and military—do not “die”; they are “martyred” or “achieve martyrdom.” To use such terms exclusively in the translation would make the memoir read like church history or hagiography. An amalgamated approach seemed to be in order. Thus, casualties in this translation more often than not “die,” but when people close to the narrator (father, brother) pass away, they are “martyred.” This is to reflect the deeply emotional impact of the death rather than to assert that the deceased is heaven-bound, which— it is believed—only God can determine. The extended passages on impending death or martyrdom in Da also entail the notion of halaliat, literally “the state of being halal or “free of sin.” The term is used when survivors ask the departed to be absolved of committing any slight, wrongdoing, or transgression. It involves a deeply felt amalgam of guilt and shame for not having behaved well toward someone. Translations can only approximate such a tangle of feelings and memories. Chapter 9, for example, has the translated Zahra begging her martyred father’s “forgiveness,” which faintly renders the emotional force and intent of the Persian. “Absolution” was a possibility, but it seemed too freighted with non-Muslim associations to be at home in the memoir of a devout Shii. An analogous use of halal comes in Chapter 12 when Zahra, sensing her brother’s martyrdom is at hand, asks her mother to “make [her] peace with Ali.” The original is shirat`ru halalash kon, literally “make the milk you fed him as a child halal.” The English compromise is cold and clinical.

Mojahedin or “Hypocrites”: Translating Monafeqin (“Hypocrites”), a staple of Sacred Defense usage, also presented a problem. As mentioned above, the narrator consistently uses this pejorative term, which is taken from the Quran, to refer to the Islamo-Marxist group Mojahedin-e Khalq. It is part of a purposeful demonization of the organization, which carried out a number of attacks on Iran’s top leadership and sided with the Iraqis during the War. On one hand, to translate Monafeqin as “People’s Mojahedin of Iran” would be to neutralize both regimist and popular hostility toward the group. On the other, using “Hypocrites” would make the translation resemble official texts. In this case the translation has erred on the side of antipathy.

Gharib: Gharib, literally “strange” or “stranger,” is another term with a long history that defies easy translation. In Chapter 9 Zahra recites a dirge in Arabic about the martyrdom of the innocents at Karbala, in which gharib is translated as “forlorn.” Zahra’s mother uses it when standing at the gravesite of her dead husband and says to him, “We’re burying you like some stranger.” Though all but one of her children are with her, the absence of her father and brothers at the funeral is almost as painful as the death of her spouse. In this way Hoseyn Hoseyni goes to a grave that will soon be overrun by the Iraqis as one “estranged” or “dispossessed.” He is not only bereft of life but abandoned—like the martyrs of Karbala—by all but those nearest to him. As in the case of other terms with deep roots in Arabic and Persian literature, the English equivalents used here cannot fully convey the intent and emotional impact of gharib.

Dagh-del: “seared of heart”: After the start of the War, public expressions of deep sorrow and grief normally reserved for Moharram pageants or for recitation of Karbala elegies became common in Khorramshahr. Da often pairs the qualifier dagh (“scalding hot”) with del (“heart, gut”) to convey these feelings. Dagh can be paired with kabab to mean kebab “straight from the grill.” A “bazaar” can also be dagh when there is a “hot market.” The terms dagh and del are often used to mark the ineffable feelings that come with the loss of a loved one. The usage is a common trope in the rich tradition of elegiac literature in Persian. In Chapter 4 a dirge describes the Prophet Mohammad’s heart as being “seared,” which once again does not do justice to the sentiment in the original. “Heartburn,” of course, was rejected for its gastric associations, and “heart-scalded” seemed a misleading neologism.

Mazlumiat va ma’sumiat: “victimhood and innocence”: In Chapter 7 Zahra describes her father’s eyes as “brimming” with mazlumiat and ma’sumiat. The English paraphrase “the look of an innocent victim” doesn’t quite capture the religio-cultural import of the phrase. Hoseyn Hoseyni has made his peace with the world. Realizing he is about to die, he formally hands responsibility for the family over to his eldest daughter. As one on the verge of martyrdom, he is innocent in two senses: “incapabable of harm” or “put upon” (mazlum) and “untainted by sin” (ma’sum). In this way he is like the holy Imams, who are considered sinless, but victimized by the forces of tyranny.

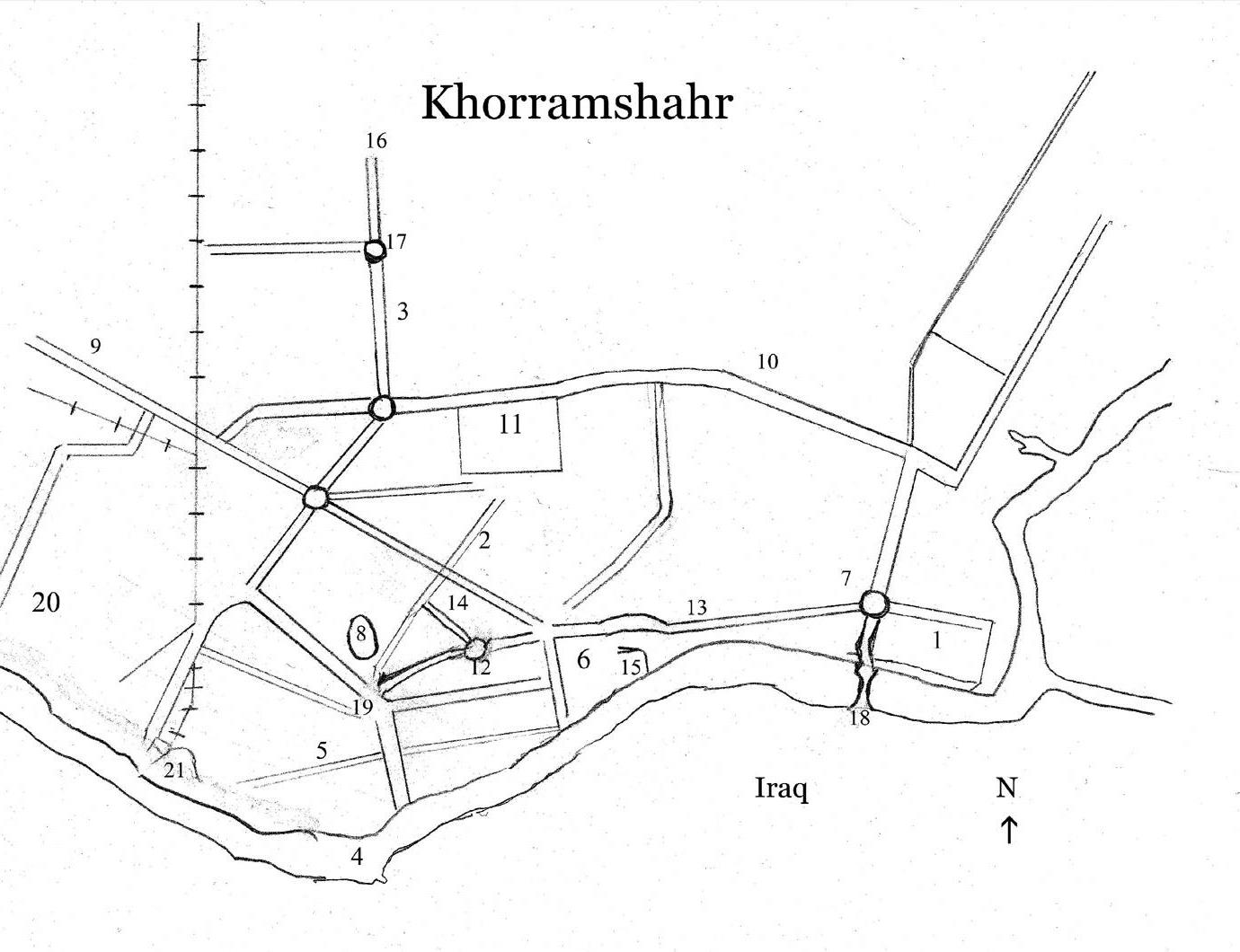

Map Legend

The map of Khorramshahr, which is not drawn to scale, represents the city as it was during the initial stages of the War. It is based on the one found in Khorramshahr dar Jang-e Tulani (“Khorramshahr in the Long War”), Mehdi Ansari, Mohammad Dorudian, and Hadi Nakha’i. Tehran: Markaz-e Motala’at va Tahqiqat-e Jang, 2006, pp. [176a-b].

Legend

1. Mosaddeq Hospital

2. Persian Gulf Avenue

3. Dieselabad

4. Shatt al-Arab (Arvandrud)

5. Ferdowsi Avenue

6. Congregational Mosque

7. Farmandari Circle

8. Stadium

9. Road to Shalamcheh

10. Ring Road

11. Jannatabad

12. Darvazeh Traffic Circle

13. Forty Meter Road

14. Hafez Avenue

15. Safa Market/Bazaar

16. Road to Ahvaz

17. [Road] Police

18. Bridge

19. Moqbel Circle

20. Port and Customs Area

21. Sentab Gate

To be continued …

Number of Visits: 3418

http://oral-history.ir/?page=post&id=10633