Memoirs of Commander Mohammad Jafar Asadi about Ayatollah Madani

Selected by Faezeh Sasanikhah

Translated by Kianoush Borzouei

2024-9-16

As I previously mentioned, alongside Mehdi, as a revolutionary young man, there was also a cleric in Nurabad, a Sayyid, whose identity we had to approach with caution, following the group’s security protocols, to ascertain who he truly was. We assigned Hajj Mousa Rezazadeh, a local shopkeeper in Nurabad, who had already cooperated with us, to discreetly investigate this cleric—who he was, where he came from, what he was doing there, and what his ideological stance was. Attending just one Maghrib and Isha prayer behind this cleric in the mosque was enough for Hajj Mousa to uncover the whole story. A few hours after the Maghrib call to prayer, he returned and told us that the man was Ayatollah Madani, from Azarshahr in Azerbaijan, exiled to this place by the regime from Khorramabad.[1]

The next evening, along with Mehdi, Mahmoud, and Mousa, we joined him for prayers, and afterward, using the pretext of asking about the difference between mutlaq and mudhaf water, we approached him. Gradually, we introduced ourselves and became his students and disciples, forming a bond of loyalty that endured not only until his final breath but continues even today, as we long for just one more moment in his presence.

Early on, we learned that after completing his primary education in Azarshahr, he moved to Tabriz, then to Qom, and eventually to Najaf, where he became one of the close disciples of Ayatollah Khoei. I later saw with my own eyes his ijtihaad decree, penned by Ayatollah Khoei himself. When Imam Khomeini was exiled to Najaf, Ayatollah Madani, with his pure heart, gravitated towards him. On one occasion, he even complained to his teacher, Ayatollah Khoei, saying, “Your status in Najaf surpasses that of Ayatollah Khomeini, so why don’t you take a stance or protest as he does?”

Ayatollah Khoei responded with explanations, justifying that his role was different, that it was his responsibility to protect the seminary from political harm, and that other matters were secondary. Ayatollah Madani, however, remained unconvinced, and the discussion escalated. It was a painful memory that I hesitate to dwell on. Eventually, Ayatollah Madani’s seminary stipend was cut off by Ayatollah Khoei, and whether out of necessity or a sense of duty to support Imam Khomeini’s cause, he returned to Iran to introduce the people to the Imam’s ideology and viewpoints.

From the very beginning, SAVAK (the Shah’s intelligence service) opened a special file on him. In Khorramabad, the head of SAVAK himself would call his house. Ayatollah Madani had a habit of answering the phone himself. The SAVAK officer, not revealing his true identity, would introduce himself as a government official and ask, “From which marja' should I follow?” Ayatollah Madani would provide both rational and religious arguments, explaining that shifting allegiance from one marja' to another was permissible, and that today, it was obligatory to follow Ayatollah Khomeini. The SAVAK officer then said, “But I am employed by the government, and the regime doesn’t get along with Ayatollah Khomeini!” To which Ayatollah Madani replied, “Who’s asking you to bring his treatise to work? There’s no need to tell anyone who you follow. The matter of taqlid is between you, your God, and your marja'.”

The head of SAVAK later told a merchant in Khorramabad, “That man has real courage!” The merchant relayed this to Ayatollah Madani, who responded, “Tell him I say the same thing to everyone—it’s simply my duty.”

These interactions led the Khorramabad branch of SAVAK to conclude that he should be exiled. They knocked on his door in the middle of the night, and when he came out in his house clothes, they took him away without his cloak or turban, bringing him to the police station and then exiling him under guard to Nurabad Mamasani. Outside Khorramabad, someone was sent to retrieve his cloak and turban.

During the journey, his demeanor was such that even one of the officers, following his advice, removed his gold ring, performed ablution, and prayed behind him.

In Nurabad, Ayatollah Madani was required to visit the gendarmerie daily to sign in and confirm his presence in the city. Every day, between 11 a.m. and noon, he would walk to and from the gendarmerie. I offered to drive him, saying, “Sir, it’s hot, and you’re not young anymore. Let me take you by car.” He insisted on walking. I suggested he go early in the morning when it was cooler, but he raised his eyebrows and said, “No, this time is just fine!”

At first, I didn’t understand why he insisted on walking this route at this hour. I followed him once or twice and noticed that on his way back from the gendarmerie, he would stop by a high school, lean against an electric pole, catch his breath, and as soon as the school let out, students would gather around him. I asked him why he did this. He replied, “These are young people with pure hearts. Just by wondering why this Sayyid has to go to the gendarmerie every day to sign in, they’ll become aware of the injustices of this regime.” With these high school students, he would often engage in lighthearted conversations and jokes rather than religious sermons, believing that the youth would naturally discover the truth. He used to say, “If a thief breaks into a house, he’s not worried about the old people waking up; he’s more concerned about the young ones. In our house, the thief is the U.S., taking away our wealth, dignity, and honor. We must awaken the youth.”

From the second month of his exile in Nurabad, Ayatollah Madani began conducting Quranic exegesis classes. These sessions were held three nights a week after Isha prayers in his rented house next to Imam Sajjad Mosque. In the beginning, there were only five or six of us, and we agreed that each of us would bring two more people for the next session. By the second week, there was hardly any room left in the house. The discipline and order at these classes were extraordinary. If anyone was even a minute late, they couldn’t enter, as the door would be closed at the start of the lesson. In the third or fourth session, which was dedicated to the exegesis of Surah Al-Fatiha, a passionate young local said, “Sir, I wish you would start with Surah Al-Tawbah since it’s about jihad!” Ayatollah Madani smiled and said, “You seem very eager for battle, young man! Don’t rush! The Quran is a book about how to live. If someone learns how to live well, every moment of their life will become a jihad in the path of God.”

I still remember the examples he gave in his classes. One night, pointing to the lamp hanging from the ceiling, he said, “If someone has no knowledge of electricity, they might think this lamp shines on its own. But in reality, its light comes from the power source. If the lamp’s connection to the power source is cut even slightly, it won’t emit the faintest glow. Likewise, if a person’s connection to God is severed, they will have no light.” He then spoke about the importance of prayer in seeking spiritual light, sharing the story of the night when Khadijah (peace be upon her) found the Prophet (peace be upon him) not in bed, but outside, lying on the ground and crying, “O God, do not leave me to myself, even for the blink of an eye.”

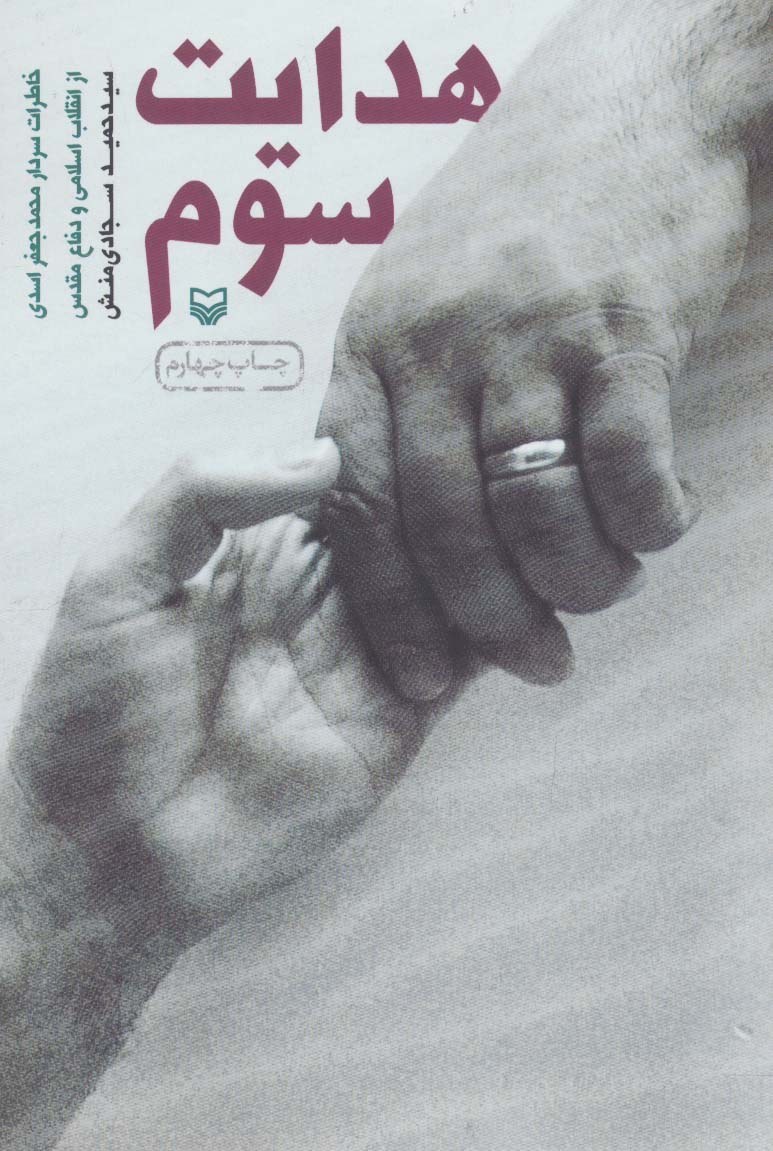

Source: Sajjadi-Manesh, Seyed Hamid, "The Third Guidance," Memoirs of Commander Mohammad Jafar Asadi from the Islamic Revolution and Sacred Defense, Tehran, Soore Mehr Publications, First Edition, 2014, Tehran, p. 59.

[1] After the victory of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Seyed Asadollah Madani, at the invitation of the people of Hamedan, moved to this city and was elected by their vote to the Assembly of Experts for Constitution. After the martyrdom of Ayatollah Ghazi Tabatabaei, the first Friday prayer leader of Tabriz, he was appointed by Imam Khomeini (may he rest in peace) as the representative of the Supreme Leader and the Friday prayer leader of Tabriz. Finally, on September 11, 1981, at the age of 68, he was martyred by the hypocrites (MKO) in the Friday prayer pulpit of Tabriz and was buried in the shrine of Lady Masoumeh (peace be upon her).

Number of Visits: 325

The latest

- Exiling Hujjat al-Islam Wal-Muslimeen Mohammad Mahdi Roshan to Zabul

- The 359th Night of Memory – 2

- What will happen for oral history in the future?

- Oral History Does Not Belong to the Realm of Literature

- Da (Mother) 124

- Memories of Muhammad Nabi Rudaki About Operation Muharram

- Study and Research as Foundations for the Authenticity of Narrators

- The 359th Night of Memory – 1

Most visited

- Da (Mother) 123

- Imam’s Announcement in the Barracks

- Night raid and brutal arrest

- Study and Research as Foundations for the Authenticity of Narrators

- The 359th Night of Memory – 1

- Memories of Muhammad Nabi Rudaki About Operation Muharram

- Oral History Does Not Belong to the Realm of Literature

- Da (Mother) 124

Destiny Had It So

Memoirs of Seyyed Nouraddin AfiIt was early October 1982, just two or three days before the commencement of the operation. A few of the lads, including Karim and Mahmoud Sattari—the two brothers—as well as my own brother Seyyed Sadegh, came over and said, "Come on, let's head towards the water." It was the first days of autumn, and the air was beginning to cool, but I didn’t decline their invitation and set off with them.

The interviewer is the best compiler

According to Oral History Website, Dr. Morteza Rasoulipour in the framework of four online sessions described the topic “Compilation in Oral History” in the second half of the month of Mordad (August 2024). It has been organized by the Iranian History Association. In continuation, a selection of the teaching will be retold:The Last Day of Summer, 1980

We had livestock. We would move between summer and winter pastures. I was alone in managing everything: tending to the herd and overseeing my children’s education. I purchased a house in the city for the children and hired a shepherd to watch over the animals, bringing them near the Karkheh River. Alongside other herders, we pitched tents.Memoirs of Commander Mohammad Jafar Asadi about Ayatollah Madani

As I previously mentioned, alongside Mehdi, as a revolutionary young man, there was also a cleric in Nurabad, a Sayyid, whose identity we had to approach with caution, following the group’s security protocols, to ascertain who he truly was. We assigned Hajj Mousa Rezazadeh, a local shopkeeper in Nurabad, who had already cooperated with us, ...